Context

In the beginning, there were Activities. And, for a while, things were good. Before Android 3.0, Activities were essentially God objects that oversaw large chunks of what happened in our applications.

In 2011, however, tablets started entering the market and developers needed a way of reusing code to support larger screen sizes without having to duplicate business logic (a prime example of this are master/detail flows). Thus, the Android team added Fragments, or composable Activities, in an attempt to break up these giant, monolithic Activities.

Their addition to the framework, however, wasn’t exactly welcomed with a ticker tape parade.

For both beginners and advanced developers, Fragments have always seemed a bit confusing. On top of that, Google didn’t provide much guidance as to their usage, which was sort of intended.

At Google I/O 2016, Adam Powell of the Android Framework Team gave a presentation on how to efficiently use fragments. In this talk, Adam discussed some of the common problems developers have with Fragments:

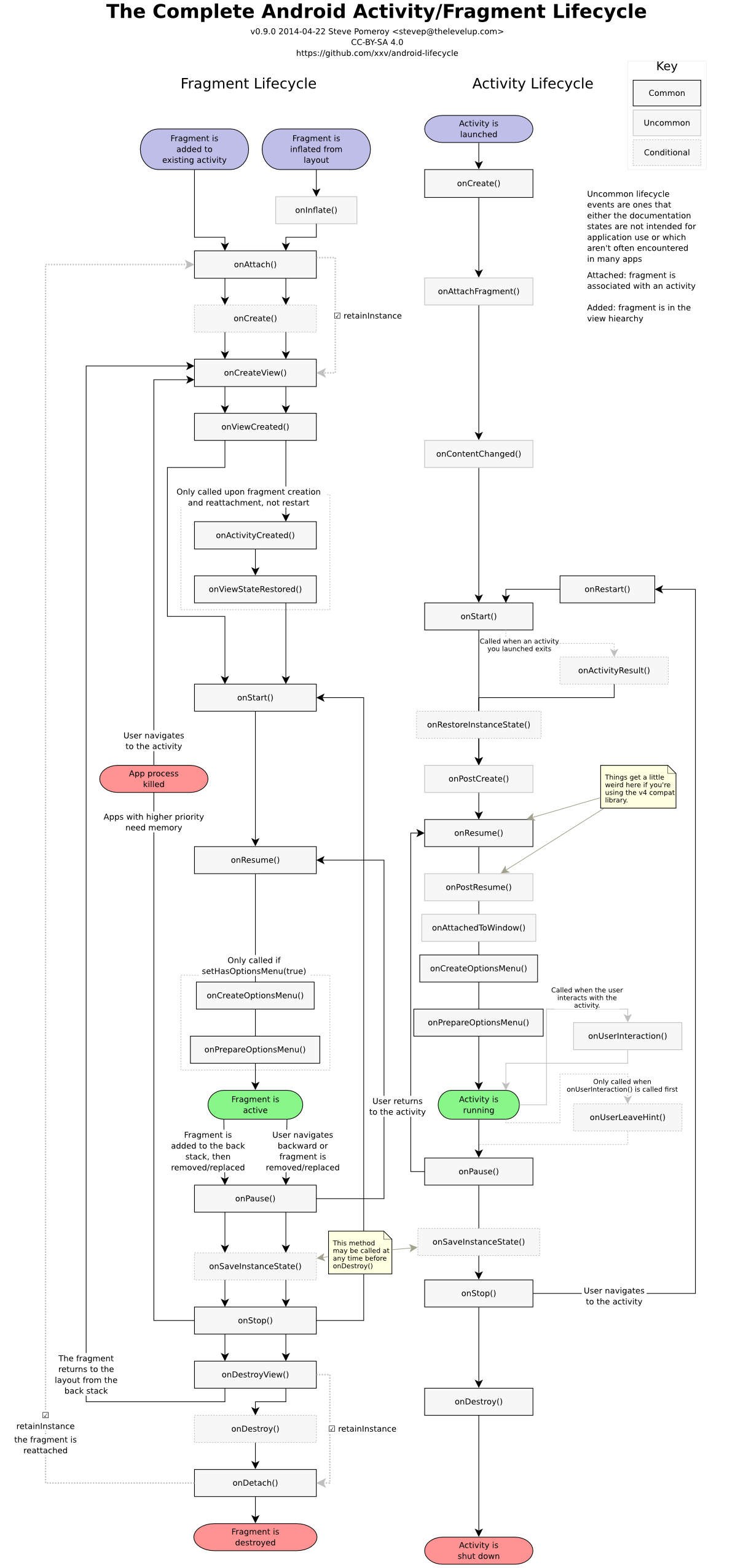

- Complex Lifecycle - The activity lifecycle is complex, and when you throw Fragments into the mix the result can be daunting.

-

Fragment Manager Transactions - Asynchronous, which can lead to unexpected behaviors (also buggy). Not to mention if you were to run into problems within a transaction, Android will throw the dreaded IllegalStateException which can be really challenging to debug.

-

Custom View or Fragment? - Confusion as to whether to use a Fragment or a custom view. The Fragment Tag hasn’t helped, either.

Adam argues that we can overcome most of these challenges if we think about Fragments in a couple of different ways:

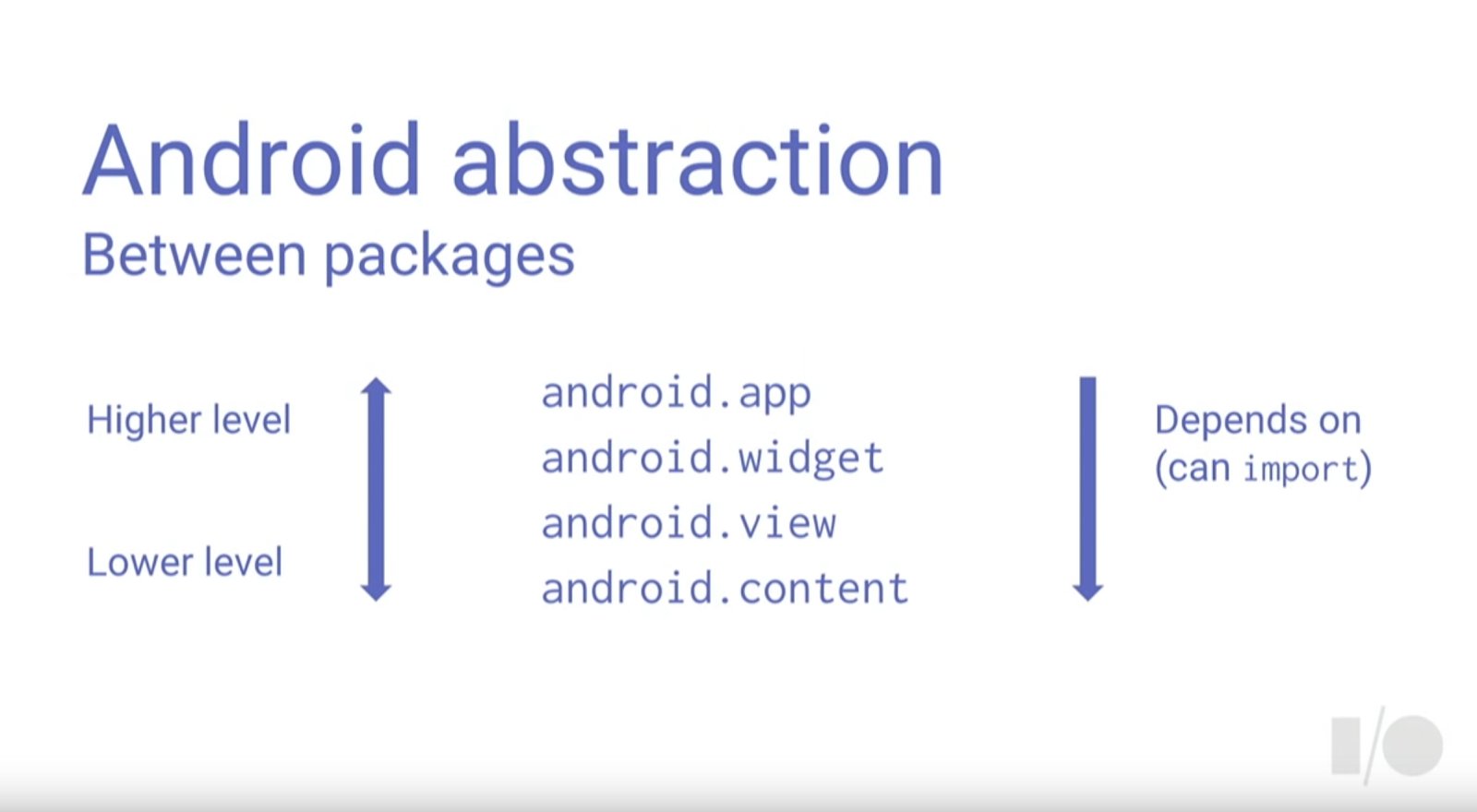

First, Fragments, like all the other android components, are simply composable entry points into an application. In fact, they are the same as Activities in terms of abstraction. The smaller and smarter we write Fragments, the less they are impacted by their surroundings.

Second, Fragments are not fancy views. Fragments use views to implement UI, but you can have Fragments that don’t use views, and that’s perfectly ok. In practice, Fragments should depend on views and respond to events that happen within views. Likewise, views should have no knowledge of Fragments.

Fragments should coordinate between other Android components and be the enforcer of application business logic.

But after years of trying to incorporate Fragments, developers started to grow restless and longed for an alternative.

The Rise of Fragment-less Architecture

Square - Advocating Against Fragments

In 2014, roughly three years after the addition of Fragments to the Android Framework, developers from the company Square wrote a rather scathing blog post advocating against using Fragments. In addition to some of the problems with Fragments we have already discussed in this post, Square cited problems debugging the Fragment Manager and exceptions that can occur when fragments are recreated.

But instead of just pointing out the flaws with Fragments, Square decided to do something about it and built tools to make it easier to create applications without Fragments - Flow and Mortar.

Flow is a library that allows you to describe your UI, called a “screen,” using a simple POJO class. A screen needs only to know with which View it will be associated with and any methods needed to update the view. Flow also gives you a basic navigation stack, independent from the Activity and FragmentManager backstacks and much simpler. This allows you to navigate and persist state when moving back and forth between screens.

If Flow encapsulates the UI and provides a navigation stack, where do we put our business logic? What if we need to hook into the lifecycle? That’s where Mortar comes in. Mortar is a library that uses the MVP pattern to wrap up business logic into presenters and interact with views. Each presenter is scoped, thanks to Dagger, so that resources are cleaned up if a presenter gets destroyed. Mortar, also, gives you a very scaled back lifecycle to manage the life of a presenter.

There are a lot of positives that Flow and Mortar give us:

-

No Fragments

-

Forces modular and testable code through MVP and Dependency Injection

-

Memory efficient due to Dagger scopes

Unfortunately, at the time of this blog post, there are some rather large negatives:

-

Very steep learning curve - If you are not familiar with Dagger/Dagger 2 or the MVP pattern, you might feel like you’re climbing a mountain before you get anywhere.

-

Lots of boilerplate code.

-

Both libraries have had a very long release cycle:

-

It has been a year since the last minor update to Mortar.

-

Flow finally hit 1.0.0-alpha in February 2016 followed by the latest release, Flow 1.0.0-alpha2, in September.

-

Square’s blog post and libraries ignited a fire in the android community. In the wake of the post, it seemed as though two communities instantly formed: those who wanted to use design patterns to make Fragments easier to work with and those who never wanted to use Fragments again. Let’s take a look at the anti-Fragment camp first.

Down With Fragments

A popular pattern for developing applications with Fragments is Fragment Navigation Pattern, or the “One-Activity-Multiple-Fragments” architecture. If your app is structured using this pattern, then you might be able to switch back to using multiple activities. If you are not using this pattern and are just trying to move away from Fragments, you could consider a custom view instead. There are challenges, however, with both of these approaches.

In the case of switching to multiple activities, one area of interest we would need to pay extra attention to is how we optimize interfaces to support different form factors (such as tablets). Android gives us the ability to qualify resources for the particular screen sizes, which would work great for simple layouts. But what if you wanted to implement a master-detail interface where the experience is different between devices? You may find yourself coding special logic to handle each form factor or even creating entirely different activities to solve the problem.

But this approach can lead to interfaces that are tedious and difficult to maintain. One of the nice things about Fragments is they allow us to isolate our UI components so activities could focus on everything else. Could custom views give us the same benefits?

The short answer is yes, unless we have to worry about the state of our UI. Remember, one of the goals of Activities (and Fragments as an extension) is that they always stay in the state where you left them. There are several items to consider if you decide to implement custom views:

-

View State In the case of orientation changes, the view will be destroyed and recreated. To save the state of your view, you now need to override the onSaveInstanceState and onRestoreInstanceState methods on each custom view and save the view’s state into a parcelable.

Managing a view’s state becomes less tedious using libraries like as Icepick or AutoValue with the Parcelable extension. The goal of both of these libraries is to eliminate the boilerplate needed to create a Parcelable.

-

Managing the backstack How do you handle the back button? Depending on the use case, you may want to emulate the behavior you get with Fragments.

For example, say you wanted to navigate between two views within a single activity and return to the same state using the android back button or toolbar. The FragmentManager allowed us to push Fragments onto a historical stack and manually call popbackstack, returning to the previous state, whenever the user pushes the back button. Views don’t have a similar construct. We either have to rely on the Activity’s stack or implement a custom solution.

The concept of a view backstack becomes even harder if you want to move from a “Single Activity - Multiple Fragment” architecture into a “Single Activity - Multiple View” architecture.

In the wake of Flow and Mortar, there are now a couple of libraries that can help deal with these scenarios.

Simple Stack

Long time anti-Fragment advocate Gabor Varadi has written extensively on topics pertaining to living without Fragments and how Flow’s backstack work. In 2016, Gabor forked Square’s Flow library to add notable enhancements and fixes into a library called Flowless. Ultimately, fundamental limitations in Flow’s design drove Gabor to create his own backstack.

The result is a library called Simple-Stack. Simple-Stack is a backstack library that allows you to represent and navigate between the states of your application. The Backstack class keeps track of the UI with simple Java parcelable objects that represent the UI.

In the same vein as Flow, you can change the state of the application by invoking the Backstack’s goTo(<key>), goBack(), and setHistory() methods. The backstack is persisted through the BackstackManager which allows it to survive configuration changes and process termination.

For specific examples on how to use Simple-Stack, take a look at Gabor’s Master-Detail, Fragment, and Nested Stack samples.

Conductor

Conductor is a library that describes itself as “a small, yet full-featured framework that allows building View-based Android applications.” Some have described it as a much better implementation of Fragments.

Similar to Fragments, Conductor is architecture agnostic. You can use it with any of the MV* pattern.

Out of the box, you get the following features:

-

Controllers, which are simple Java classes that wrap views and give you access to a simplified lifecycle.

-

A backstack, called a router, that allows you to navigate between Controllers.

-

State persistence. Controllers are retained during configuration changes.

Long Live Fragments

As Square mentioned, it’s difficult to test Fragments, especially in isolation. Yet, through Mortar, Square showed how it is possible to decouple the business logic and view code from the Android lifecycle, making their presenters testable. Even though Square wasn’t the first to start using design patterns on Android, after their blog post, the Android community finally seemed ready to utilize these patterns for cleaner and more testable code.

There are a lot of resources for learning these design patterns:

-

Eric Maxwell recently posted an excellent primer on the MV* patterns.

-

The Android Architecture Blueprints GitHub repository has examples of using MVP both with Fragments and without.

-

Google has started to use the MVP pattern in their testing CodeLab.

Smarter Fragments

During Adam’s talk on Fragments, he mentioned how Fragments are easier to work with when they are small and isolated. We have now seen what Square was able to accomplish with Flow and Mortar and we have also discussed how design patterns can make our code more testable. Unfortunately, unless you are working on a brand new application (or have a large maintenance budget), you are likely going to be maintaining an existing application that uses Fragments.

Until there comes a time when a library or component is created to complete replace Fragments, and you have the budget to revisit your legacy applications, there is certainly something we can do today to make Fragments easier to work with and increase testability and coverage. The idea is to make our Fragments smarter by moving decoupling the business code from the android code. We can then unit test our business code to obtain deeper code coverage within our application.

As an example, let’s create an app that lists the github repositories for a given user – in this case me (myotive). You can find the code for this example here. The code for this sample was inspired by the Google Architecture Todo MVP Dagger sample.

Utilizing MVP, I have a presenter which interacts with a model (the GitHub API) and a view interface. In this case, I’m going to have the Fragment implements the view interface to handle updating the UI.

public class RepositoryContract {

public interface Presenter<T extends BaseView> extends BasePresenter<View>{

void getRepositories();

}

public interface View extends BaseView {

void updateRepositoryList(List<Repository> repositories);

void onRepositoryItemClick(Repository item);

}

}Using a Dependency Injection framework (in this case Dagger 2), I can inject the presenter directly into the Fragment since we are unable to do constructor injection with Fragments.

public class RepositoryFragment extends Fragment implements

RepositoryContract.View

{

@Inject

RepositoryContract.Presenter presenter;

@Nullable

@Override

public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater, @Nullable ViewGroup container, @Nullable Bundle savedInstanceState) {

View view = inflater.inflate(R.layout.fragment_repository, container, false);

// obtain Dagger 2 ActivityComponent from Actiity

ActivityComponent activityComponent = ((MainActivity)getActivity()).getActivityComponent();

// Inject dependencies

activityComponent.inject(this);

presenter.setView(this);

...

return view;

}

}By injecting the presenter into the Fragment, I have isolated the presenter and view logic so I can test each independently from the Fragment using any unit testing framework. This gives me more code coverage within the Fragment.

public class RepositoryUnitTest {

@Mock

private RepositoryContract.View view;

@Mock

private ProgressBarProvider progressBarProvider;

@Mock

private GitHubAPI gitHubAPI;

@Mock

private Call<List<Repository>> mockCall;

@Captor

private ArgumentCaptor<Callback<List<Repository>>> captor;

private RepositoryPresenter presenter;

@Before

public void setup(){

MockitoAnnotations.initMocks(this);

presenter = new RepositoryPresenter(gitHubAPI, progressBarProvider);

presenter.setView(view);

}

@Test

public void test_getRepositories() {

// arrange

String user = BuildConfig.GITHUB_OWNER;

List<Repository> repositories = new ArrayList<>();

repositories.add(new Repository());

when(gitHubAPI.GetRepos(user)).thenReturn(mockCall);

Response<List<Repository>> response = Response.success(repositories);

// act

presenter.start();

// assert

verify(mockCall).enqueue(captor.capture());

captor.getValue().onResponse(null, response);

verify(progressBarProvider).showProgressBar();

verify(progressBarProvider).hideProgressBar();

verify(view).updateRepositoryList(repositories);

}

}Conclusion

Fragments aren’t perfect but have come a long way since their addition to the Android framework. Regarding Fragments in 2017, the community is at a crossroads thanks to the efforts of Square and developers like Gabor, which isn’t a bad thing. Healthy discussions and alternative points of view can only make the developing experience on Android better.

Fragments still provide a construct for reusing UI, breaking up monolithic activities, and working within the Android lifecycle. Today, a lot of the bugs surrounding Fragment Transactions and Child Fragments have been fixed. And we can make Fragments smarter by moving business code into testable structures, such as presenters. This makes dealing with framework issues (such as state restoration) become less of an issue.

However, if you are completely fed up with Fragments, you have options in 2017. Consider giving libraries such as Simple-Stack and Conductor a try. Both will allow you to build flexible, View-based applications.

Receive news and updates from Realm straight to your inbox