Do you want to contribute to Swift? Not sure how or where to begin? It can be overwhelming! In this talk from the inaugural try! Swift conference, Jesse will help you explore the different parts of Swift, see how the various Swift projects are related, discuss the skills you need to get started, and learn the best ways to get your first fix accepted.

Introduction (0:00)

This post will cover quite a few different things: we’ll talk about different parts of Swift and different projects, a little bit about LLVM, the skills you need, and how/why you should contribute. Hopefully, Swift will feel more approachable after you’ve read this.

Where to Start? (0:53)

Apple surprised us when they announced that Swift was being open sourced. There are lots of different projects within it. It wasn’t just the compiler, but also the core libraries, the standard library, and the formal Swift evolution process. The great thing about this is that there’s something for everyone, so you don’t have to be a compiler expert to contribute.

However, all of that can be overwhelming, and it’s hard to know where to start. How do all of these different pieces fit together? A high level overview of how the compiler works can help situate you within a project and within the area that you want to contribute to.

What happens when you compile your code? (2:18)

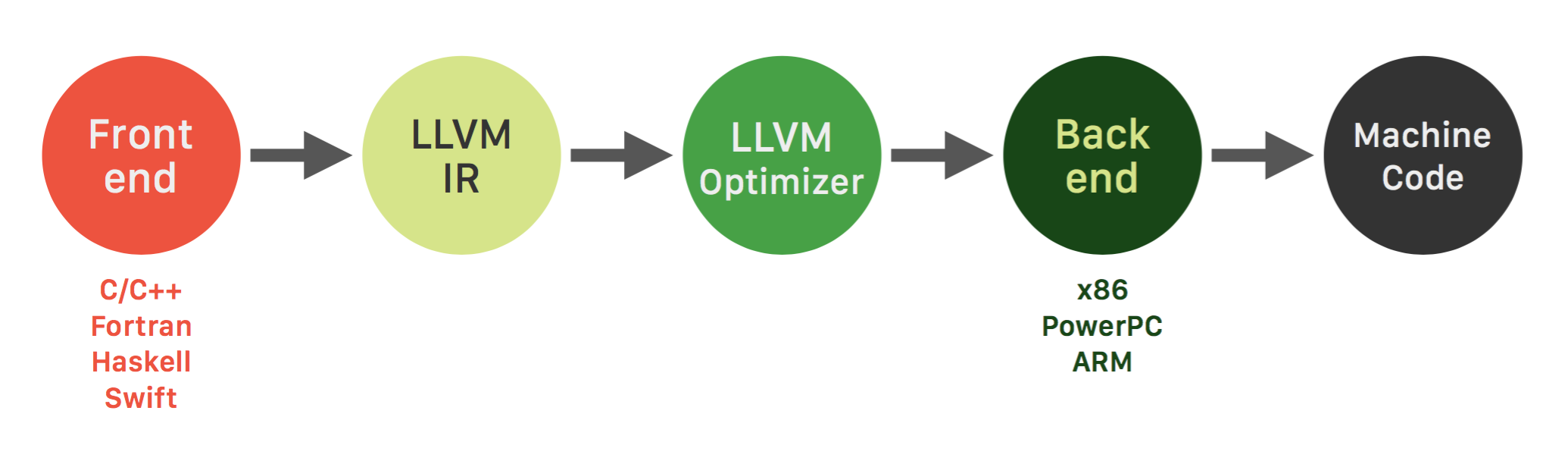

Swift is built on top of LLVM, created by Chris Lattner. How do we get from writing code to a native, executable binary?

-

We begin with a front end, or a specific language.

-

The front end is responsible for parsing source code and producing LLVM IR (“Intermediate Representation”). This is how LLVM represents your code in the compiler. IR is a high level assembly language that is independent of architecture. It is important to note that it’s a first class language with well-defined semantics.

-

From there, LLVM IR is handed off to an optimizer which performs various analyses and optimizations to improve the code.

-

The optimized IR is then sent to a back end, which is responsible for producing native machine code based on the architecture or instruction set specified by the back end.

LLVM is very modular. The language and parsing are actually decoupled from producing your binary, with this LLVM IR layer in the middle. It has been a very popular project for this reason.

Clang pipeline (4:28)

Before Swift, there was Clang. Clang is a C, C++ and Objective‑C front end to LLVM. Its pipeline begins with C or Objective‑C source code. We take that source code and parse it into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), a tree representation of your code. The AST then goes through semantic analysis for optimization. The modified AST is then handed to a code generation phase, which produces IR. The IR is then handed off to LLVM and the pipeline described above, which then produces our binary.

I won’t delve into Clang architecture, but there are some legacy issues. It’s not as clean as I’m describing it. The parsing and semantic analysis are a bit intertwined, and there’s some code duplication. It’s a great tool, but it’s not quite the cleanest. This has informed the Swift compiler in a lot of ways.

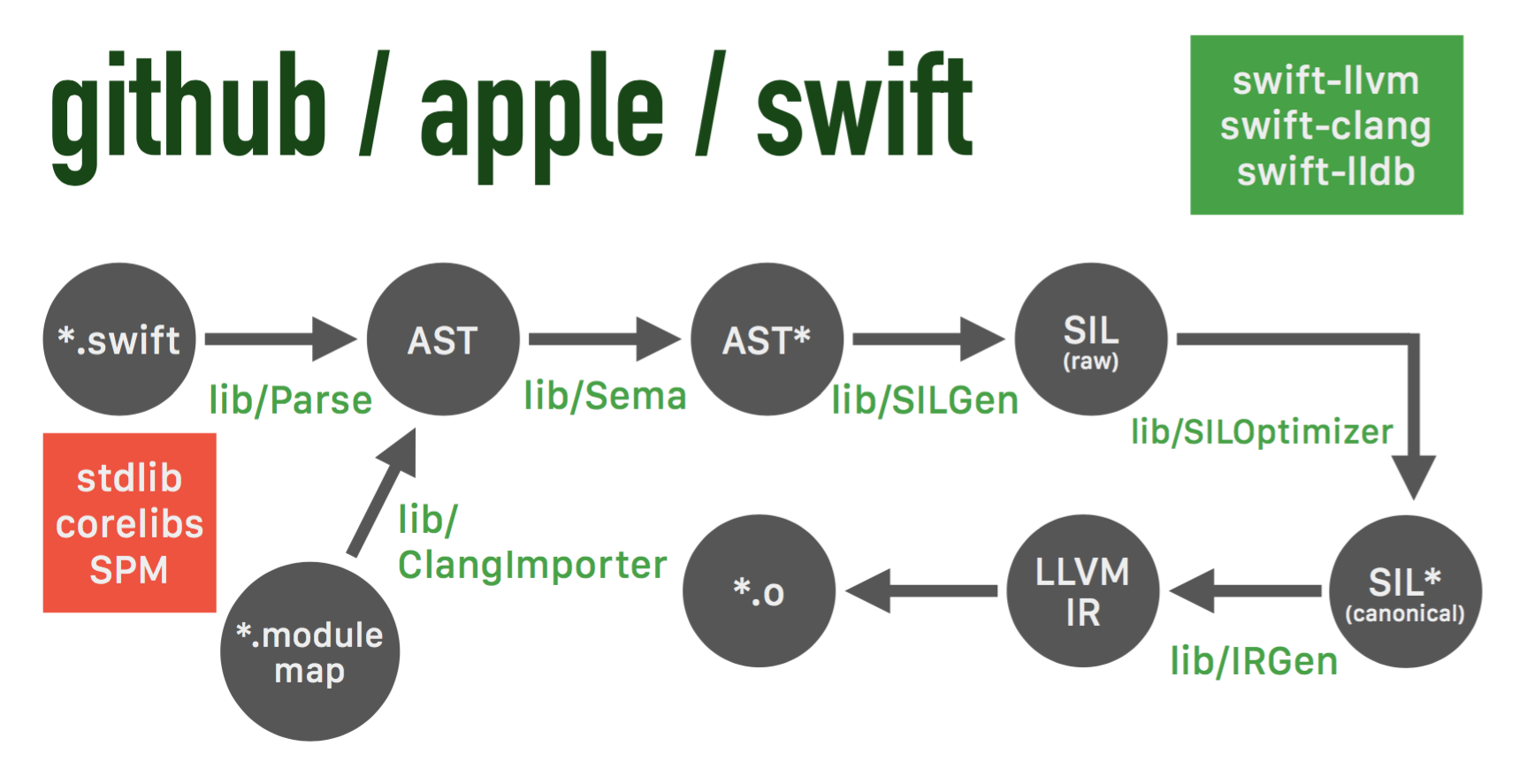

Swift pipeline (6:34)

The Swift pipeline has incorporated a lot of lessons learned from Clang, and has tried to avoid some of the mistakes.

We begin with Swift code. That code is parsed into an AST, similar to what Clang does. The AST also goes through semantic analysis, and this phase is responsible for taking the parsed AST and transforming it into a well-formed and fully type-checked form of the AST.

At this stage, we can also emit warnings and errors for semantic problems in the source code, which is then handed off to the Swift Intermediate Language (SIL) generation phase (similar to LLVM IR.) SIL is basically a Swifty wrapper around IR.

SILGen produces raw SIL, which then goes through analysis and optimization. This is where most of Swift’s “Swiftiness” comes from. Since we have an intermediate layer there, we can do lots of optimizations in that phase. There are Swift-specific optimizations, arc optimizations, devirtualization, and other things that can happen. This produces canonical SIL, which is then passed off to the IR Generation phase, and produces LLVM IR. It is handed off to LLVM to complete the process like before.

Module maps are another piece of this, which has to do with how we interoperate with C and Objective‑C. You’ve probably seen (or at least heard of) module maps. We take Clang modules, pass them through the Clang importer, and their resulting ASTs can be referred to through semantic analysis. This is what makes interop possible.

I realize the above descriptions seem like a lot. Compilers are one of the more challenging areas of computer science. I am not an expert in them, and truly, no one is an expert in every single one these phases. Even the people on the core team have specialized areas throughout this pipeline.

A Brief Example (10:05)

// hello.swift

print("hello swift!")>swiftc hello.swift

>./helloWe have our basic Hello World program, which we can compile and run from the command line. We can actually produce and examine the AST like this:

>swiftc -dump-ast hello.swiftThe resulting AST is pretty crazy. You can try it with your own code. You can also emit SIL using this command, in which we demangle the symbol names. (If you’re not familiar, Swift uses name mangling.)

>swiftc -emit-silgen hello.swift

| xcrun swift-demangleReading SIL is kind of like reading assembly language. It’s very verbose, but not too hard to follow. We can also emit LLVM IR and assembly as well:

>swiftc -emit-ir hello.swift>swiftc -emit-assembly hello.swiftAgain, you don’t have to have expert knowledge in all of these areas to contribute to open source, but I do think it helps to see this at a high level and understand the pipeline as a whole.

Projects and Repositories (12:20)

The pipeline we examined before breaks down into projects, basically. Within the main Swift repo, we have subdirectories for each phase of the pipeline.

If there’s a specific area you’re trying to work in, contribute to, or file a bug report for, you can use this as a map of where to look.

Off in the corner, we have LLVM, Clang and LLDB, since they’re kind of their own thing. At the beginning of the pipeline, we have the standard library, the core libraries, and the Swift Package Manager. This should make sense: these are Swift and C libraries that are fed through the pipeline, either parsed through Swift or through the Clang importer, just like you would write your own code and compile it.

For each project, I’ll list a difficulty rating. These ratings may be slightly subjective, but also relative to all the projects.

Swift core (14:46)

Compiler Difficulty: Hard Language: C++ GitHub Activity: High

If you’ve never written or used C++ a lot, it can be challenging and more nuanced than Swift. It actually has a lot of the issues that Swift tries to address, like undefined behavior.

stdlib Difficulty: Medium Language: Swift* GitHub Activity: Medium

This is what we all use. The asterisk next to Swift is because it’s slightly different than normal Swift. In stdlib, you have direct access to LLVM built-ins, the primitive types in LLVM IR.

SourceKit Difficulty: Hard Language: C++ GitHub Activity: Low

Finally, SourceKit, as we know, is what powers Xcode syntax highlighting and never crashes 🙄. This is in C++, so it’s more challenging.

Swift infrastructure (16:03)

LLVM, Clang, and LLDB Difficulty: Very Hard Language: C++ GitHub Activity: Low

These three projects are part of the LLVM umbrella project, but they are Swift-specific clones of these projects with some small Swift-specific changes. These are very hard to contribute to, since they require the deepest compiler and Clang/LLVM knowledge. I think these are mostly settled until Swift 3.

Another important note here is that all of these projects are governed by the LLVM Developer policies, coding standards and licensing: they’re not really part of the Swift brand of projects. In many cases, a contributed change may not be specific to Swift, so you actually need to contribute those changes upstream to the parent projects. These are synced regularly with LLVM.

Package Manager (17:34)

swift package manager Difficulty: Medium Language: Swift GitHub Activity: High

Package Manager is all in Swift, which is really nice. The barrier is low in that respect, but it does wrap a lot C libraries. There’s a lot of interop with C, and that may not be familiar to everyone.

swift-llbuild Difficulty: Hard Language: C++ GitHub Activity: Low

Then we have llbuild, which is a low level build system. It’s a set of libraries for building build systems (meta, right?). This is generally a more challenging project.

Core libraries (18:17)

Foundation Difficulty: Easy Language: Swift, C GitHub Activity: High

XCTest Difficulty: Easy Language: Swift GitHub Activity: High

libdispatch (GCD) Difficulty: Hard Language: C GitHub Activity: Low

I think the core libraries are probably the easiest to get started with. These are familiar, since we’ve used these from Objective‑C. They’re mostly in Swift, but with some C and C-interop. Just as Objective‑C foundation wraps the C level core foundation, Swift does the same.

Swift evolution (18:49)

Finally, Swift evolution contains the formal process for fundamental changes to Swift. Anyone from the community can write a proposal. This repository also contains the development and release schedules, so it’s a good place to stay updated on what’s coming up in each release, what’s planned, what is intentionally not planned, etc.

If you are submitting proposals, they should really provide tangible benefits to the community. You need to be thoughtful, and you should vet them on the mailing list first. There have been a few cases where someone says, “I want this feature,” but they don’t really give a good reason why. If you want to push for a change in Swift, you really need to have a good argument for it, and try to build support from the community.

Contributing (20:14)

Discussion about contributing needs to happen on the mailing lists, and issues should be submitted on the JIRA Bug tracker. Neither of these should be done on GitHub. This is important for documentation reasons: it’s easy to start discussing things on a pull request, but the core team asks that most discussion is kept in JIRA and the mailing lists.

You should read the contributing guidelines and try to do it right. The best way to have your changes accepted are to follow those guidelines.

That being said, there are tons of ways that you can contribute, and it doesn’t just have to be code. Aside from new features and bug fixes, there’s documentation, translation of documentation, fixing typos, tests, etc. All of these things massively help the community.

Typo fixes may seem small, but they are important. Non-native English speakers find clear text easier to understand, and typos make that more difficult. Typo-free documentation is also easier to translate. Any time you see a typo, submit a quick pull request and it’s going to be a huge help.

Furthermore, opinions matter from every level. It doesn’t matter whether you’ve been programming for 20 years or 20 days: your perspective matters. Chris Lattner has made it clear on several occasions that Swift is not only intended to be a great language to replace Objective‑C, but a great language for beginners as well.

Pro Tips (23:14)

A few pro tips on contributing, since most of our interaction with the core team is on Twitter, GitHub, or the mailing lists:

-

It’s important to be kind

People will disagree on the mailing lists. Don’t be mean. Respect other people’s opinions. Keep in mind that it’s easy to misread or misunderstand text, so someone may be saying something other than what you’ve interpreted.

-

Ask for help

There are tons of places to do this. All of us are on Twitter, and we’re there to help. The mailing lists are also there as a resource.

-

Follow best practices

Especially when submitting a pull request: include tests, make sure your code is clean, do all the things that we know how to do. It’s going to be way easier for the person who has to review your code if you follow best practices and guidelines.

-

Rejected? Don’t stop contributing!

Don’t get discouraged. Whether a proposal or a pull request is rejected, it doesn’t mean you’re a terrible person. It just means that it’s either not the right time, or it’s just not right for Swift. Keep in mind that the core team really knows the big picture: they’re guiding these projects, and sometimes they may know things that we don’t. A rejected proposal or pull request is not the end of the world, and it happens to everyone, even the top contributors.

-

CODE_OWNERS.txt

Each project has one. This will tell you which core team member owns which part of the code base. Tag them in your pull request. That will save everyone a lot of time, and your changes can get reviewed and hopefully accepted much faster.

-

No one is an expert in everything!

It’s okay to ask questions, and it’s okay to not be perfect at everything. I can’t stress enough that the core team wants to accept your changes. They want everyone to participate. They will work with you on a pull request to try to get it accepted in any way they can. As long as you receive their feedback well and make the changes they ask, they will merge your changes if it’s right for Swift.

A good way to start is to follow examples. There are some really great people in the community that don’t work at Apple, yet have done some great work. They found their area of expertise. I encourage you to find part of Swift or the other projects that you’re passionate about, and focus on that aspect. That will make you a successful individual contributor, and it will support the success of Swift as a whole.

Everything starts with a small change, and small improvements are how everyone gets involved. This is a huge deal for the core team, because Swift’s success depends on community participation.

Why Contribute? (28:20)

I think it’s pretty clear that Apple is hugely invested in Swift. It’s not going to disappear anytime soon. This is the next generation of iOS and Mac OS development, and maybe more. Swift can and will be whatever we want it to be as a community.

The entire process is completely open, and the core team is so receptive to our feedback that we have a chance to make Swift the language we want. As individual developers, Swift’s success is our success; Swift’s portability is our portability. The more platforms that Swift is available on, the more places we can use our skills to build all kinds of apps.

We’re still in the very early days of Swift, but we can ask ourselves:

“What do we want Swift to be like in 10 years?”

These first few years are definitely the defining moments of Swift, and we have the power to decide where the language goes. It’s more than just the compiler, the code, and the libraries. It’s also how we write, and what the Swift best practices are. That’s implicit in all of these contributions: what’s the best way to write good Swift?

Swift is much more than just a programming language. It’s a community full of awesome people who want to build awesome things. Don’t be afraid to contribute or ask for help. The best thing you can do is try!

Receive news and updates from Realm straight to your inbox