When the Instagram team rewrote their iOS feed from the ground up, they learned more than they anticipated about collection views, diffing, and the dangers of too much spaghetti code. In this talk from try! Swift, Ryan Nystrom shares his story of what it takes to ship a successful refactor, and introduces Instagram’s open source gift to us all: IGListKit.

Introduction (0:00)

I’m Ryan Nystrom, an engineer in New York working on Instagram. We’ve been doing a lot of really cool work on infrastructure. For the past year, I’ve been working on rebuilding how our feed works on Instagram. It’s been a really fun process and we’ve learned a lot. Whenever I go to conferences, I love listening to other industry experience talks because I think it’s fascinating to see how other companies and organizations work.

I want to share a bit about how we work at Instagram through the lens of this story of rewriting our feed.

Technical Debt (1:29)

Why did we rewrite our feed? In short: technical debt.

Instagram is a 6.5 year old app, but the code base is still the same. If you search through the git history and blame some files, you’ll find some Instagram init code commits in there. There are still a couple pockets of manual memory management, and there’s a lot of mess. There were a lot of things that made it really challenging.

How did it work? (2:05)

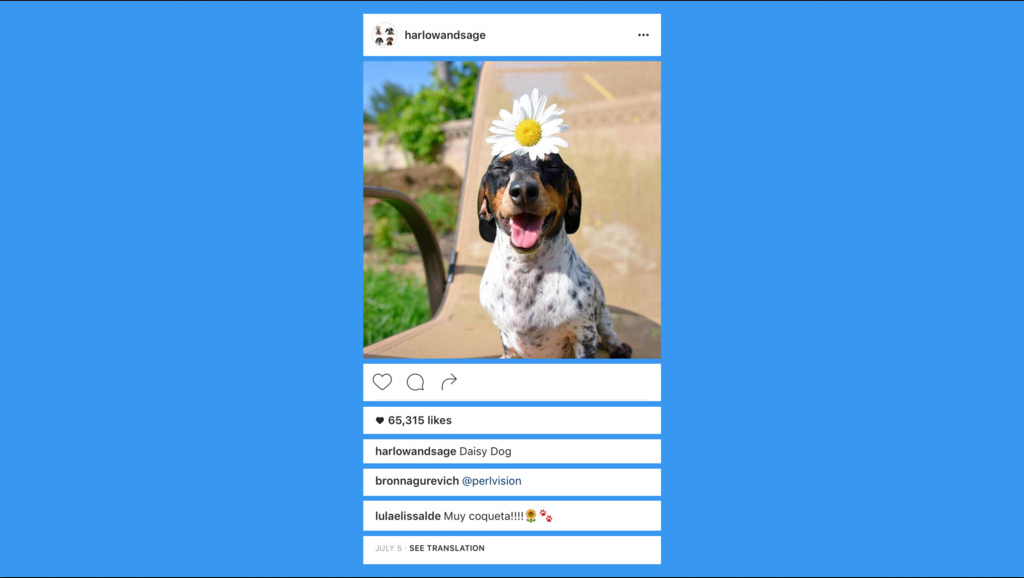

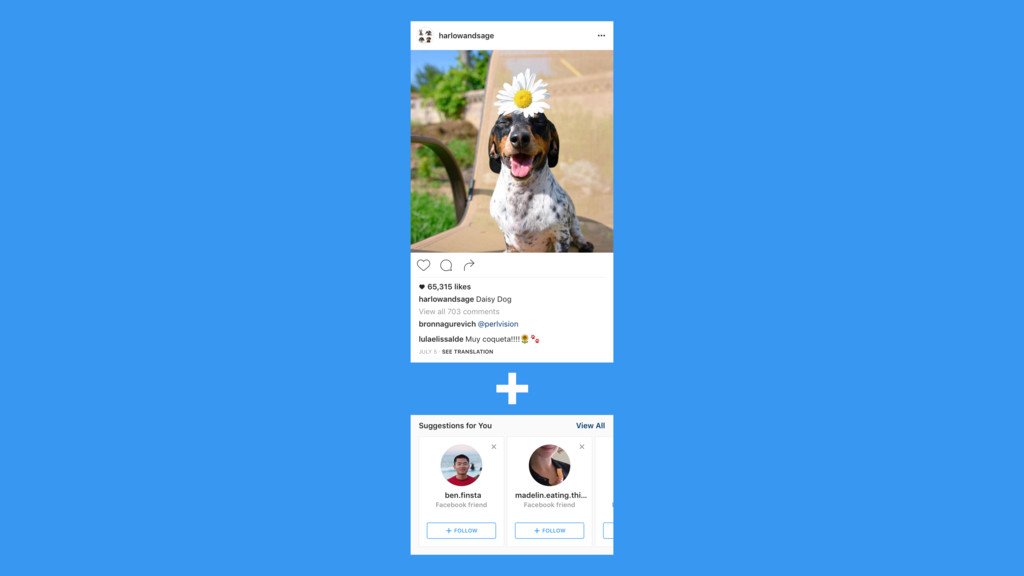

For starters, we use collection views. When we’re looking at a post on Instagram, we see a big section and we break it up into multiple smaller cells. This breakdown works something like this:

You’ve got a supplementary view at the top, you’ve got a cell for the media, a cell for all the action items, and then all these text cells at the bottom. This is driven by a data model that we call a “feed item”.

You have a single feed item that decides how many comments there are, if we’re going to show an image, if we’re going to play a video, what the user’s name is, etc. Our entire app is built around this feed item data model, and it expects this feed item to have an image, a video, comments, etc. When somebody comes along and says, “Hey, we want to add a new item to the feed,” but it looks like this, we have to say, “sorry, can’t do it, it’s not a feed item”:

It’s a cell, somebody designed it, and a product manager worked on it, but it has an array of users, no comments, and it didn’t make any sense. It sucked to tell our teammates “no.”

Just Slap it On (3:41)

Instagram launched back in 2010, with just the images. Over time, we’ve had people come along who wanted to add stuff like video, users, and other sorts of data models. I’m sure we’ve all experienced wanting to make one little change, instead of refactoring and doing what we know is right… we’d like to just slap it on.

Well, that’s what we did. Instead of having all these extra individual tiny contained models, we had a huge model. It became really difficult and started to slow us down. Now remember this section cell mapping is driven by a feed item. If you’re looking at a feeds in Instagram, you’re not looking at one post: you’re seeing a bunch.

Something needs to take this data model, put it into a section, and configure all these cells. That was the responsibility of our view controllers. (Yes, that’s controllers in the plural.) We had a view controller for our collection view, inherited from that we had a view controller that did our networking, inherited from that we had a view controller that does general feeds, and then if you’re on the main feed tab of the app, we had a view controller for that too. Four levels deep. Adding a new cell was tough.

You may think “So you’ve got a little bit of spaghetti code. Maybe it slows you down once in awhile, but is it that bad?”

Yeah, it can be pretty bad. Technical debt can bite you. We decided that we needed to get really serious about it, so we created a new feed that we launched about three months ago.

Feed 2.0 (6:35)

Our main goals were to fix that view controller inheritance, make the feed way less complicated, and also let people use different cells and data models. We wanted to get rid of the “feed item” idea, something that was totally agnostic of our data types.

Diffing (7:10)

We started with diffing, which is a concept where you have an array of things such as a set of models. You go to another array here stuff’s been deleted, inserted, or moved around, so its values update. Diffing is super helpful when building infrastructure, but to get it right with collection view is pretty tough.

First off, you have to delete things in the old array, then you reload, move anything into its final position, and then do your inserts based on the final index. To do it well takes a little bit of math.

Most naive implementations of diffing are in complexity n². When you’re doing that many operations, it can be slow. Most implementations I’ve seen will go to a background queue, do the math, come back to the foreground and carry on, but even that is kind of slow. You’ve got a lower priority queue solving a harder problem. Why not just do it on the main thread?

Well, we went searching and we found a paper written in 1978, by a guy named Paul Heckel. This paper solved this problem in linear time using something called the least common subsequence.

By doing this, we created an algorithm that will find all the deletes, reloads, inserts and moves between two sets of data in linear time. It’ll let us do it on the main queue, so we could perform all of these updates on the collection view; it’s a much simpler model for us. Additionally, we figured out how collection view works, which takes a lot longer than you would think.

Applying Updates (9:35)

Back to the view controller mess, we got rid of a lot of stuff, putting it instead into shared objects, systems, libraries, etc. They don’t need to be view controllers. Networking is networking, main feed stuff like analytics and all that can just be in an object. But we still had to deal with the feed.

This used a concept we call “The World”, where the view controller knows about the array of items, how those items get into sections, how those sections are configured, and how the cells populate. It deals with interaction, logging, display events, and all that stuff.

Item Controller (10:28)

In the new infrastructure we created, we decided to split things up. We created an abstraction called an “item controller”. It’s literally just a little view controller for a section.

This is where you decide the number of items, configure your cells, return your cell size, and deal with interaction. But most importantly, it’s where you store all your business logic. It’s nothing fancy, it’s just a collection view, but when we split things up this way it lets us add any other type of object to our collection views.

All you have to do is create a new item controller, and it handles it for you.

We thought it was impossible, but we figured it out. The team was happy and we shipped this along with our new infrastructure.

What can we give back? (11:26)

After we built it, we realized we solved a lot of really complicated problems, so we asked what we could give back to the community. We wanted to address how we solved the more complicated problems.

IGListKit (12:48)

We are open sourcing a brand new framework that does all of this for you, called IGListKit(release tba).

All of our sample apps and documentation are written 100% in Swift, using Objective-C nullability, annotations, and generics. This is 100% Swift compatible; all the C++ is buried so far away you’ll never have to see it.

IGItemController (13:34)

One of the most important classes in this framework is called IGItemController. It’s the “item controller” concept I mentioned at the beginning. It’s not a whole lot of code. This just does a single cell that has a text label. That’s it.

To actually use this, we create an item controller and conform to the IGListItemType protocol:

class LabelItemController: IGListItemController, IGListItemType {

...

}At compile time, this protocol will make sure you implement all the important methods, like returning the number of items:

func numberOfItems() -> UInt {

return 1

}In Instagram’s main feed, we have a dynamic array for the image, the comments, and the action bar. You return the size. Notice too that we have a context object:

func sizeForItemAtIndex(index: Int) -> CGSize {

return CGSize(width: collectionContext!.containerSize.width, height: 55)

}This cell is the width of the screen or the width of its container, and 55 points high. Next, this is a new concept, different from collection view. We have this didUpdateToItem:

var item: String?

func didUpdateToItem(item: AnyObject) {

self.item = item as? String

}This is where the infrastructure will hand your item controller the model. With the mapping, we had all of these models that were mapped to item controllers. In this case, we’ve got an item, we optionally cast it as a string, and we store it in an instance variable. Then we take that instance variable, and in our cell for an item at index, we dequeue the cell, we set the text on the label and we return it, just the same as collection view’s data source.

We’ve gotten rid of the concept of reuse identifiers, and we’ve completely eliminated the need to register cells and supplementary views. So that’s it, that’s an item controller. But what good is an item controller, without some infrastructure, without something to use it?

IGListAdapter (15:42)

We have an IGListAdapter:

//MARK: IgListAdapterDataSource

func itemsForListAdapter(listAdapter: IGListAdapter) -> [IGListDiffable] {

return [

"Foo",

"Bar",

"Baz"

]

}

func listAdapter(listAdapter: IGListAdapter, itemControllerForItem item: AnyObject) -> IGListItemController {

return LabelItemController()

}This is what will take your data, all of your item controllers, your collection view, put it all together and make it work. To use this, you just have to connect the data source.

In the first method, we’re just returning an array of stuff. Here, they’re all strings. They can be anything. Notice that the return type is IGListDiffable. We’ve provided default implementations for this protocol, so everything works out of the box. However, you can override and extend that protocol to do whatever you want for even smarter diffing. Now there’s another method that for any given item, we return an item controller. We’re just returning that same label item controller that we looked at previously.

Say we wanna add a spinner while we’re waiting on a network request to come in. We can create a token object (here’s just an NSObject called spin token), and we can throw it right in the middle of that array. It’s just a protocol, so we can put any sort of model objects we want in this. Then, when the infrastructure asks us for the item controller, we check “is that item the spin token”? If it is, we return this new spinner item controller. Otherwise, just fall back to the labels:

func listAdapter(listAdapter: IGListAdapter,

itemControllerForItem item: AnyObject) -> IGListItemController {

if item === spinToken {

return SpinnerItemController()

} else {

return LabelItemController()

}

}It looks like a spinner, right in between our cells:

This may not seem that exciting, but I get excited about the diffing. Imagine we’ve got a UISearchBar. As a user types and changes the text, we want to update these results:

func searchBar(searchBar: UISearchBar, textDidChange searchText: String) {

filterString = text

adapter.performUpdatesAnimated(true, completion: nil)

}So here in the searchBar delegate method, we store the string in an instance variable and call performUpdatesAnimated. This tells the infrastructure to get those new items, diff them, and update the collection view.

We can also filter our array:

let words = ["Foo", "Bar", "Baz"]

func itemsForListAdapter(listAdapter: IGListAdapter) -> [IGListDiffable] {

return words.filter { word in

return word.containsString(filterString)

}

}We take our array of strings, filter them for our string here, and return it. This is in the data source method, because it will only be called when you tell the infrastructure to update. It performs inserts, deletes, moves, everything on the collection view. I didn’t write a single line of code for that collection view; I just configured my cells, my item controllers, and I told my adapter to update. I get all these animations and updates out of the box.

Why use IGListKit? (19:15)

Say I’ve got a simple app, I’ve got a table view, I call reloadData. Does this matter? Well, I think you should use it if you’ve got multiple data types in the feed. If your feed is getting complicated, if you’re tired of dealing with integer enums for your sections, like I am, this is for you.

If you want a fast and crash-free feed that has animated updates, this will work really well. It also encourages you to write reusable components, from your cells to your item controllers, plus your view controllers.

I could drop an item controller I’ve written in one location and drop it in any other view controller or setup in my app, because they’re agnostic of their containers. I also love never having to call performBatchUpdates or reloadData again in my life.

You might think “Well, Instagram built this, should I use it?” Well, in a span of about 15 minutes, we do 3.9 million diffs in the world with no crashes, all on the main thread, crazy fast.

Where do we use it? (21:13)

This entire project started because we wanted to rewrite our main feed. Now, our explore page with all those grid items, our activity feed, and even the complex cells and interactions in our direct messaging product are using IGListKit. Instagram stories, which we launched about a month ago, uses it, and that little tray and the fullscreen items are 100% built in IGListKit. We are fully committed to using this framework. It is the future of our app.

IGListKit coming soon

I hope that in sharing some of the story of how we work at Instagram, you’ll be able to take away something and apply it to the apps you’re working on in your organizations. I am really excited to see what you’re able to build with IGListKit!

Receive news and updates from Realm straight to your inbox